Famous for: In 1870, Stevens along with Van Trump become the first successful documented climbing party to summit Mount Rainier.

Also notable for: Serving in the Massachusetts state legislature, receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor for the capture of Fort Huger, Virginia in the American Civil War, and representing American interests against the British in settling San Juan Islands boundary dispute.

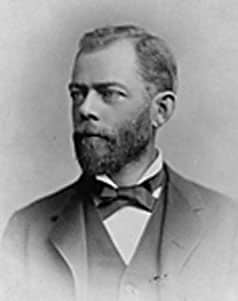

Hazard Stevens

Born in Newport, Rhode Island in 1842, Hazard Stevens came west in 1853 when his father, Isaac I. Stevens was appointed first governor of Washington Territory. At a young age Hazard traveled throughout Washington Territory accompanying his father meeting with tribal leaders and establishing treaties. When the American Civil War broke out, both father and son joined the 70th Highlanders of the New York Volunteers. At the Battle of Chantilly (VA) on September 1, 1862, Isaac was killed and Hazard wounded. The younger Stevens recovered, returned to battle and on April 19, 1863, was instrumental in the capture of Fort Hugar, Virginia for which he received a Congressional Medal of Honor.

With daylight diminishing, they crossed the summit crater where they found a cavern warmed by sulfur steam providing them shelter for the night.

Hazard Stevens returned to Washington Territory after the war. In August of 1870 he along with Philemon B. Van Trump made the first successful documented ascent of Mount Rainier. The two had a fascination with the mountain and planned for years to summit it. On August 8, 1870 they accompanied by Edmund Coleman (who in 1868 became the first person to summit Mount Baker) left Olympia for their expedition. They stopped in Yelm for pack horses provided by James Longmire, and in Bear Prairie they met their Yakama Indian guide, Sluiskin.

After a difficult crossing of the Tatoosh Range in which Coleman lost his pack and turned back, Sluiskin, Stevens and Van Trump continued to Mazama Ridge. At this point Sluiskin tried to convince the two not to go farther, convinced that an infernal demon on the mountain would destroy them. The three set up camp that night at a point (site of the Stevens-Van Trump Historical Monument on the Skyline Trail) just above what is now Sluiskin Falls.

At 6 a.m. the next morning Stevens and Van Trump left for the summit. Equipped with staffs, a rope, ice axe, gloves, goggles, food, a canteen, a brass plate with their names inscribed, and a couple of flags they began their ascent. They did not take their jackets and blankets however, believing they would return before nightfall.

They climbed past what is now Camp Muir and up to the base of Gibraltar Rock. From there they continued along a narrow ledge to the ice and glacier above Gibraltar Rock. At 5 p.m. they thought they had reached the summit, but were actually on what is now referred to as Point Success, which at 14,158-feet is about 250 feet lower than the true summit, Columbia Crest. With daylight diminishing, they crossed the summit crater where they found a cavern warmed by sulfur steam providing them shelter for the night.

The following morning after a miserably cold night they reached Columbia Crest, where Stevens left the brass plate at a boulder. They then made a difficult descent returning to their camp hungry, cold and tired. Stevens made a fire and roasted marmot that Sluiskin had killed for them. Sluiskin joined them later that evening not sure if they were real flesh and blood or ghosts from the infernal demon. Finally convinced it was the men in the flesh, Sluiskin kept repeating, skookum tilicum, skookum tumtum; roughly translated as strong men with brave hearts.

Once back in Olympia they were well received. Stevens published newspaper articles accounting their climb convincing most folks that they indeed reached the summit of Rainier. Some folks however remained skeptical of the claim, and Stevens’ brass plate has never been found.

In 1874 Stevens returned east to Boston and served in the Massachusetts state legislature. He ran unsuccessfully for the US Congress. He returned to Olympia each year to oversee management of his Cloverfields Farm (now on the National Historic Register). In 1905 through a trip organized by the Portland-based Mazamas, he made a successful second ascent of Mount Rainier. He passed way in 1918 at the age of 76. Stevens Creek, Stevens Ridge and Stevens Canyon are all named after him.

[authorbox authorid=”7″ ]